It looked like I would finally get to see some action. I had been in the Army for more than two years, and all I’d been doing is training, guarding, patrolling, teaching, and traveling. But it would still be several months before I’d get to actually meet the enemy. First debarkation training in San Francisco; clambering over the side of ships burdened with over 60 pounds of gear, using flimsy cargo nets, then a long voyage on a crowded, smelly, noisy ship to Hawaii, then from there to New Zealand, and then Australia. My destination would ultimately be New Guinea.

The Aussies were an interesting bunch; rough boys who had already seen hard fighting in North Africa, where water was so scarce they had to wash their uniforms in gasoline! There were a lot of ‘re-treads’, guys who had been wounded and were recovered enough to be sent back into battle, who had been fighting the ongoing struggle since July ’42, for control of the islands of New Guinea. North of Australia, NG was strategically the logical jump off point for any invasion of Australia. The Japs had attacked NG in March of ’42, as part of their major offensive that included Pearl Harbor. By mid ‘42 they were firmly established and were threatening the mainland, only 400 miles away by air!

When General Douglas MacArthur had arrived in Australia in March ’42, he was hailed as a savior. His confident bearing belied the truly perilous situation that the Japs’ advance through the great arc of islands, taking the Philippines, Raubal, Singapore, and now New Guinea, had created. MacArthur was further dismayed to discover that very few US personnel were actually in Australia at this time; he had expected to take command of a huge force being assembled in Australia to recapture the Philippines. Now it looked like he was expected to “make something out of nothing”. President Roosevelt, in meetings with Churchill and Stalin, had decided on a ‘defeat Germany first’ policy, and the Pacific Theater of Operations would not receive the men and materiel needed. Only two US Infantry Divisions were promised, the 41st and the 32nd, both National Guard divisions that hadn’t been fully trained or equipped; they were due to arrive in April and May ‘42.

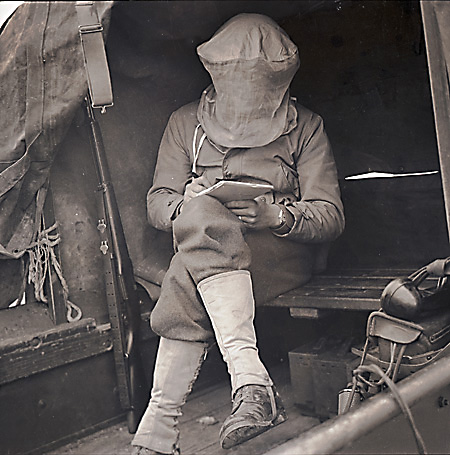

We were told the Japs were experts in the use of gas and chemical warfare, and had to train using our old gas masks.

There was no such thing as jungle battle dress at the time; we had to make do with our sun tans, the American khaki summer uniforms, which we had dyed green by an Aussie brewery! We often had to live on Australian rations: bully beef, hardtack and tea!

I was sent to various training camps and learned amphibious landing techniques, mostly using smelly old wooden fishing boats, with no debarkation ramps, just ‘over the side’! In Tasmania we trained for two weeks with rubber dinghies; living on the beach behind a perimeter of concertina wire. When we first arrived we all wondered what we had done wrong, but we were informed that this upcoming mission required secrecy, hence the segregation from the civilian population. On the first night, dusk brought a flock of horse drawn wagons to the perimeter; the local women, hearing that there was single men in the vicinity, brought us all kinds of home baked goodies, and made small talk with the boys through the fence. These gals’ hubbies and sweethearts had been away at war for a long time; they were lonely for male company.

My tent was closest to the wire, and as the Sarge, I was supposed to supervise the encampment after dark. Human ingenuity being at it’s best when concerned with matters of love, we dug a small tunnel leading from my tent to the wire, and in ones and twos my lads crept out each night for a nocturnal trysting. I stayed behind, taking my marriage vows to heart, but as my tent was the road to paradise and I the gatekeeper as it were, upon returning each GI brought me an offering from their brief romantic encounter, and I was enjoying home cooked fare for the entire stay. The training was hard, with large wooden crates simulating the ammo and rations, and lengths of pipe for our weapons. We would spend the entire day repeating the landing procedure until no one lost a single crate or weapon. We all suffered from sand and sun burns; I experimented with wearing different outfits rather than the bathing trunks that we were issued, and finally settled upon jeans with the cuffs tied closed using string.

Upon finally embarking on the actual mission, we were met at the landing site by the Captain of a PT boat, who insisted on towing the entire flotilla of rubber rafts all the way upriver, because there were no enemy in the vicinity. The total two weeks of training for the raft landing was in vain, but because of the evening’s entertainment you would never be able to convince the landing team of that! We spent several days in the jungle, but no enemy were sighted.

When I arrived on New Guinea in early ’43, the tales of jungle battles at remote outposts such as Buna and Gona, and the treacherous crossing of the Owen Stanley Mountains were already legendary among the few surviving ‘Old Men’. It took us Yanks quite a while to learn to understand the Aussie slang, but we respected the Diggers for their toughness in battle, and their ever-present good natures. ‘G’day t’ya cobber! Got tea?’

I learned all sorts of Aussie songs and jokes, and they in turn loved my version of “Pistol Packin’ Mama”, complete with harmonica accompaniment. But before I would actually get into battle, another strange little adventure awaited me in New Zealand.