We were about to make an amphibious landing on an island called Biak, off the northern coast of New Guinea. This would be my fifth landing, and it looked like it could be a rough one. Biak was a shitty little malaria and typhus infested atoll about thirty miles long; we landed near the main town of Bosnik, built by the Dutch. The Japs had a couple of airfields there, which MacArthur needed in order to strike at the Philippines with his long range bombers. But he had greatly underestimated the strength of the Japanese garrison on Biak. Captured records show close to ten thousand highly trained veteran troops on the island. The landing was lightly opposed, with sporadic fire and artillery from the massive coral cliffs that were facing the beach. Due to unforeseen strong currents on the beaches, several of the assault waves landed two miles from the designated beachhead. This required large troop units to literally march through each other on the narrow beach below the cliffs. A captured Japanese officer’s diary described the confusion as “a masterpiece of American amphibious tactics!” At one point in the chaos the Japs actually mistook one of our bulldozers clanking along the beach for a tank! But indeed the first tank battle of the Pacific war was fought here on Biak, where our Shermans made mincemeat of their antiquated light tanks.

Reflecting their new strategy of letting us land on the beaches and then drawing us into ambush, the Japs were dug in with well-concealed positions in caves and bunkers, tunnels and trees. The Japs hadn’t been here long, only a couple months, but they had made excellent use of the subterranean system of caves that varied in size from a hallway to a five-story building! Forgotten eons ago rainbow schools of fish swam through the corals and ridges that had been up-thrust by repeated volcanic convulsions to produce this labyrinthine system of caves, now filled with weird stalagmite and stalactite formations. These ancient caverns were also now filled with thousands of fanatic Imperial Jap soldiers and marines, able to appear and vanish at will on the battlefield; equipped with their artillery, mortars, machine guns, ammo dumps, and even wood houses for the officers!

The 41st Division had by now got a reputation for ruthlessness and expertise in jungle fighting. Originally called the ‘Sunset Division’, we were now known by the press as the ‘Jungleers’. Our shoulder patch was a representation of a setting sun; we were the sunset to the Jap flag’s rising sun motif. But recently Tokyo Rose had given us a new nickname: the “Butchers of Biak”. In her nightly radio broadcasts she would berate our alleged brutality, and try to destroy morale by predicting our impending doom. A captured Jap order directed the beheading of all American prisoners.

We were spread out along a narrow track through the jungle, seeking as usual to engage the enemy. The jungles on Biak weren’t generally as thick as other parts of New Guinea, but long spidery vines choked the trees like giant nightmare cobwebs, while 200 foot evergreens clawed at the heavens, and eight foot kunai grass obstructed the interior plains. At this point I didn’t have my usual Thompson, for some reason I had had to turn it in and was carrying a carbine. Previously carried by a Lieutenant, this particular carbine’s wooden stock was shattered by a grenade when he was killed. I had removed the splintered bits of the shoulder stock and smoothed it down, and then with a Jap rifle’s cleaning rod heated red hot, had bored a hole in the pistol grip part of the wood. I then looped a piece of wire through the hole and attached a rifle sling. This arrangement allowed me to carry the cut-down carbine over my neck and hanging across my chest like you would carry a camera or binoculars.

We had been on the track in the steaming heat for several hours with no contact, when we walked right into an ambush! A squad of Japs came charging out of the snarled jungle to our left.

Coming straight at me a few yards away was a Jap Lieutenant with his bloody Samurai sword held high in the air over his head, screaming Tenno Banzai! I reflexively jumped into the brush at the right of the track, but to my surprise there was a solid wall of bamboo trees, and just as if I had hit a trampoline, was bounced right back onto the path and landed just at the screaming Jap’s feet! As he was swinging the sword down for the kill, I managed to aim my sawed-off carbine and in a split second I pumped a half dozen rounds into him!

Down he went, as the noise of battle raged through the jungle around us. The sword was covered with blood, testament to its having been used earlier that day. On his belt was a leather holster containing a Nambu 8mm model 14 automatic pistol, loaded and cocked; I couldn’t help wondering what the outcome of our encounter might have been if he had chosen to use his pistol instead of the sword. I guess his Warrior Code made him choose the sword; they had a strange concept of honor and combat.

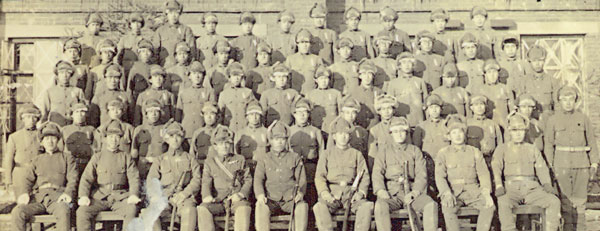

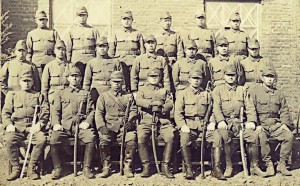

I also think they had great contempt for us; perhaps he didn’t think I was worth a bullet! Suddenly he moved as if trying to get up; I finished him off with a headshot from his own Nambu. In his map-case were several photos, and there he was in black and white, sitting with his men in a pristine winter uniform, glaring into the camera, holding the sword!

I carried that cut down carbine for a couple of weeks, but I didn’t have much confidence in its knock-down power; in another incident I emptied a half clip (8 rounds) into a big Jap marine and he was still trying to get up! As soon as I could I got my trusty Tommy gun back!

The daily combat patrols and hostile jungle climate were beginning to take their toll; we were a raggedy bunch of skin and bones; as comedian Bob Hope once said: “Army rations are meant to sustain life, not encourage it.” But the Japs were in even worse shape than we, it seemed as if only their fanatic ideology was sustaining them. During one counter attack, I saw a Jap infantryman get his entire foot blown off by mortar shrapnel, and yet he kept on charging, running on that bloody stump over sharp coral and rocks, until my machine gun cut him in two at the waist.

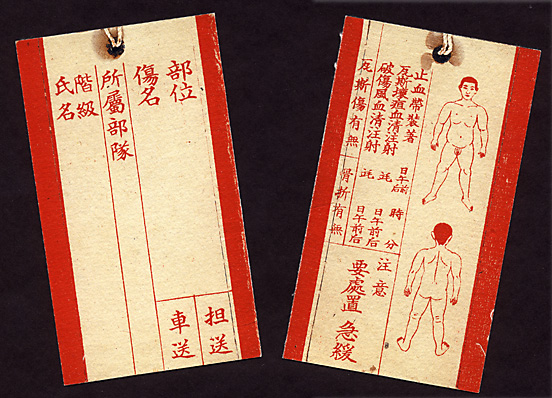

Japanese Medics

In one instance our position was attacked by two Jap medics, fully armed and determined to kill. I took several interesting souvenirs off their corpses, including photos of them in their white uniforms, a medic’s pouch with useful tins that I used for salt and foot powder, and some wounded-in-action tags with a line drawing of a Jap body on which to mark the location of wounds.

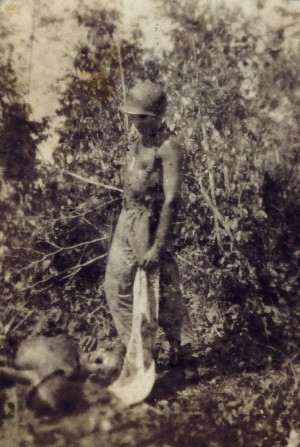

In an officer’s backpack, I found a little box camera, a German Zeiss Tengor, with three unexposed shots left on the roll. I took these shots, the only three photos that I took while in New Guinea, and HQ sent them back to me after I had turned in the film. The rest of the roll apparently had photos of some cave installations; I never saw those pics. In the three that I got back you can see me on a combat patrol, looking very skinny with a fresh killed Jap at my feet. He had jumped up out of a pile of dead bodies and charged the machine gun with his bayonet; in his cartridge pouch he had only one bullet left. I took him down with my Thompson. When I went to flip him over to empty his pockets, only the top half of his body turned; the Thompson had cut him in half at the waist! In the other two photos you can see what was left of my squad, holding up Jap battle flags, grim souvenirs of the fight.

The Japs would sign their names and sometimes addresses on the flags, before leading their suicidal Banzai charges. I wondered what they would think if they knew we used their flags to clean our guns. These attacks had a strange mystical significance to the Japs, representing the ultimate sacrifice of soldiers who preferred to die in battle rather than surrender or retreat. Typical reports from this period show marginal numbers of prisoners taken from thousands of enemy killed. One of my guys thought I was tough because I appear to be smiling in the photo with the dead Jap. I wasn’t smiling, more like grimacing; the stress was clearly showing. I was sure I didn’t have much longer and had accepted my expendability; it was just a matter of time.

I had lost fifty-two men from my squad in the eight months I had been in combat, their ghosts were beginning to loom, talking to me at night and asking questions for which I had no good answers…