Our first landing in New Guinea, though lightly opposed, still turned out to be a real bloodbath. After what seemed like days lurching in the choppy seas, I was standing at the ready in the little landing craft, right behind my Lieutenant, who was giving us the usual pep talk: “Boys, you will soon witness a lot of killing and dying; if you’re lucky you’ll be the ones doing the killing.”

The ramp had just begun to go down, when suddenly, a 20mm armor piercing shell comes straight through the steel ramp, and hits the LT in the neck, pretty much decapitating him! The blood gushed up in a fountain and blew back in the breeze; all the guys on the LCVP were getting sprayed with gore. There was all kinds of moaning and puking; these were fresh 18 year old replacements we were bringing in. Then the realization hit me: the LT was dead. I was Sergeant. I was now in charge of getting this group of men off the boat and established on the beach!

I remember I was worried about all the blood, and warned the men to wash it off ASAP or every biting insect in the area would be their dinner guests. As the ramp went down, the LT’s still twitching body fell into the well between the ramp and the fuselage; the rocking of the surf ground his trapped corpse and broke his bones with loud snaps and crunches. I got the traumatized men safely off the craft and on land, with the 20mm antitank shells, sporadic light rifle fire, and the ubiquitous snipers; but the enemy wasn’t pushing, so we advanced up the beach and into the edge of the jungle. We then established our perimeter and dug in, awaiting orders, or the Japs’ counter attack.

The Navy had shelled the entire beach in a pre-invasion bombardment, and there were craters and knocked down palm trees all over. We had established our machine gun among the huge upturned roots of one of these, and our second gun was set up among the top fronds of the same giant tree. A couple hours later, the Japs attacked in force, trying to push us back off the beach. Now I witnessed the awesome killing power of my .30 cal machine gun. Like a scythe, whole squads went down in a pile of guts and shattered bone; you could actually see parts flying off them as they charged into the hail of lead! The native Papuan ammo bearers’ eyes bugged as they cried out in shock, they covered their mouths in horror, protecting themselves from the disembodied spirits of the slain. I later learnt that they considered me a very evil and powerful man, as I did not observe the proper local headhunting customs. Henceforth, whenever I wasn’t looking, these aboriginals would abandon me and melt away into the relative safety of their jungle.

Suddenly a huge wave of Japs overran the other machine gun and began outflanking our position. Another lieutenant commands me to swing the gun around and fire into the number two gun’s position. I protest against firing into our own men’s location, but he insists, saying that all the team was surely dead by now. So I open fire, and soon the Japs there are either retreating or dead, and things cool down again. I needed to inspect the overrun position, to see for myself what had happened, and was relieved in a strange way when I saw that our guys had all taken bayonet thrusts, and were indeed almost certainly already dead before I had been ordered to fire upon them.

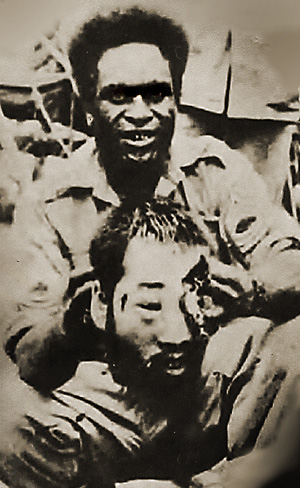

The Jap troops we encountered in New Guinea were seasoned veterans of the Manchurian campaigns; they’d been dug in on New Guinea for almost two years, and had caves and bunkers and hideouts all over the islands. Fortunately for us, since the Battle of Midway in June ’42, the Japs’ sound defeat had created a supply nightmare for their far-flung outposts. Although hardened and experienced jungle fighters, they had been starving for months, some had resorted to cannibalism, and were so under supplied they were sometimes down to their last bullets, having to use rancid coconut oil to lubricate their rusting weapons.

The next day we were ordered to advance and went out on an I&R mission, my machine gun crew attached to a rifle squad. The jungle was steaming hot, the going was slow, and the bugs were an intense nuisance. Carrying that .30 cal MG up ridges and down perilous coral and sandy tracks took a lot of energy; before long we were bushed, and dug in on a ridge for the night. Before dawn we became aware of movement in the brush; suddenly a horde of Japs came pouring from the jungle, screaming and hollering ‘Banzai!’ I waited until they were real close and started to bunch up. Then I started mowing down the ones in the rear, so as not to scatter the ones up front; I’d get to them soon! The .30 cal. poured out a stream of hot American lead, the water jacket was steaming and the gun was bucking from the recoil. With one well-aimed short burst, you could knock down 8 or 10 of them. I always fired short bursts and tried to keep half a belt of ammo for after the main wave of the attack; a lot of the time the Japs would hit the dirt when the .30 opened up, then they’d wait a while, and when their officer would blow the whistle, get up to cut a hasty retreat. Sometimes they would play possum, hiding in a pile of bodies, and then making a last desperate Banzai charge with grenade or bayonet. With half a belt of ammo left I could cut them down as they ran… Meanwhile, the boys with the BARs and Garands were picking them off as well. When they became aware of our positions, the mortars started coming in: pop, whoosh, BANG! Well, I was glad to be well dug in and behind my MG, even though the MG itself was the main target! After a few hairy minutes, they withdrew, leaving their wounded all over the little valley that they had attacked through. The wounded were screaming and hollering in Japanese; some of the boys tried to pick them off with their rifles, just to shut ‘em up. Throughout the night, the mortars kept coming in and when one of our foxholes was hit, a young rifleman was killed and two others wounded!