At Deshon General Hospital, I spent nine weeks in a GI surgical ward, with repairs being done to my shattered jaw, damaged eardrum, shrapnel peppered chest, back, legs, and right eye. During that time I saw more uncensored horrors of war. Each day new casualties from the Battle of the Bulge were being brought in. The young guy in the next bed had been hit while riding in a Sherman tank. He had lost an arm, leg, the other hand, and much of his face. His Mother had been keeping a bedside vigil for several days, and his prognosis was not very good. One day, his pretty young wife showed up and reluctantly approached his bed. When she saw what was left of her sweetheart, she screamed and fled the room. His mother entreated her to come back, but she could not bring herself to do it. He died that night.

Each night I was experiencing intense combat nightmares, and would wake up hollering for grenades and ammo, and talking to dead guys. One morning a nurse came to my bed and in my delirium, I grabbed her and threw her across the room. Thankfully, she wasn’t hurt, and I immediately apologized, but I was sent for a psych workup, and temporarily put into a psychiatric ward. The first night there, they brought in a guy wearing a straight jacket, and secured him to a bed next to mine. The entire night the guy thrashed against his restraints, chanting: “No No No No No No No No NoNoNoNoNo!” I thought, ‘if I have to take much more of this I’ll be joining him in the chorus’. The next day the shrink asked me about my battle dreams and when I told him about some of my experiences in New Guinea he said: “Joe, I think you’re entitled to have those dreams, we’re transferring you back to the surgical ward. Just take it easy on our nurses, will ya?”

Now I hadn’t been receiving my GI pay since I had left New Guinea, and it seemed that there was a SNAFU with my paperwork. One morning a finance officer shows up at my bedside, with a big dossier of files and ledgers. After ruffling through them self-importantly, this chairborne commando clears his throat and presents me with a bill, saying: “It appears you have misplaced one Browning .30 caliber water cooled heavy machine gun, with tripod and water can. You owe the Army the sum of $684.50, upon payment of which you will begin receiving your salary again.” The absurdity of this was quite obvious, but not to the pencil pusher. I explained that the machine gun was completely destroyed by the mortar shell that had injured me and killed my assistant gunner. As this didn’t satisfy him, I looked into the regulations involved, and learned that an enlisted man could not legally be held responsible for this type of equipment, which could only be signed out at the quartermaster’s by an officer. As there were no surviving officers from my outfit, eventually the issue was dropped, and I began receiving my pay again. I also discovered that it was wrong for the army to have required me to go through the dead bodies collecting material for CIC, that regulations required that this type of duty be carried out only by an officer!

After a time, I had recovered enough strength that the hospital was preparing to release me, at which point I would be discharged from army service back into civilian life.

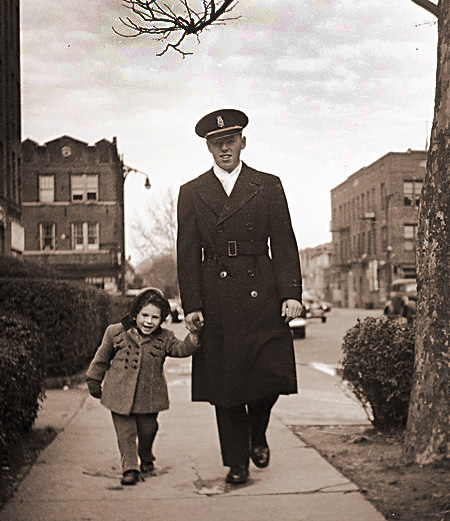

Brother Bernie Served in the Navy in Korea

I was strolling the hospital corridors one afternoon, when I saw two odd looking guys in pajamas walking toward me. As they got closer I realized that they were Japs! Without thinking, I hollered “Japs!” and leaped out the fire door into a snow bank in the courtyard and tried to get my heart to settle back down my throat. Right away a doctor came and I soon found out that these were Nisei, American born Japanese GIs that had fought in Europe, so valiantly in fact that they were the most highly decorated Allied unit in the war! The shrink later had these two Nisei visit with me to reassure me; we shook hands, had coffee and exchanged some war stories, but I couldn’t bring myself to sit at the same table and eat with them. Though they no longer frightened me, I would have these kind of bizarre reactions for some years to come; even the bang of a garbage can lid could send me diving into the gutter for cover. This was combat conditioning, and you don’t loose it easily…

One day my pal Davy came to visit, he was on leave and had managed to get back to the States for a week. “Joe,” he said, “remember that little Zeiss camera that you loaned me a while back? I want to show you some pictures that I took in Germany…”

No words can describe the pictures that Davy had taken in a concentration camp. Here they are, they speak for themselves.